Introduction: When you’re buying lumber – especially Eastern Red Cedar lumber for DIY projects – you’ll encounter a few common terms that might seem confusing at first. What exactly is a board foot? How is a square foot different? And what do phrases like kiln dried cedar or green lumber mean for your wood? This friendly guide will define these lumber terms in plain language, show you how they’re calculated (when applicable), and give real-world examples. Think of it as a cedar measurements cheat-sheet for homeowners, DIYers, and builders. By understanding these concepts, you can plan your projects and purchases with confidence, ensuring you get the right amount and type of wood for the job. Let’s dive in!

Board Foot

A board foot (bd. ft.) is a unit of volume used to measure lumber. One board foot equals the volume of a board 1 inch thick, 12 inches wide, and 12 inches long – essentially one square foot of wood one inch thick (which comes out to 144 cubic inches of wood)[1]. This term matters because many types of lumber (especially rough-cut hardwood or specialty wood) are priced and sold by the board foot to account for the wood’s overall volume[2].

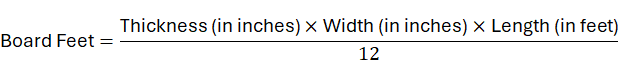

How to calculate it: To figure out board feet, you need the board’s thickness, width, and length. The formula is straightforward:

So you multiply the thickness and width (in inches) by the length (in feet), then divide by 12[3]. If you prefer to work entirely in inches, you can multiply thickness × width × length (all in inches) and then divide by 144 – you’ll get the same result.

Example: Let’s say you buy an Eastern Red Cedar board that’s 1 inch thick, 6 inches wide, and 8 feet long. Using the formula: (1″ × 6″ × 8′) ÷ 12 = (1 × 6 × 8) ÷ 12 = 48 ÷ 12 = 4 board feet. That means the board contains 4 board feet of lumber. If a certain cedar lumber is advertised at, for example, $3 per board foot, that 1×6×8 board would cost about $12 (because 4 board feet × $3 per bf = $12). Understanding this helps you estimate cost and compare prices when lumber is sold in random widths or thicknesses. Woodworkers also use board feet to figure out how much material a project needs – it’s very handy when you’re buying rough lumber or having wood milled to order.

Why it matters: Board feet account for all three dimensions of a board – thickness, width, and length – making it a fair way to measure and price wood of various sizes[2]. For example, two cedar boards might both be 8 feet long, but if one is much wider or thicker, it contains more wood and will have a higher board foot measurement (and cost) than a thinner one. By using board feet, lumber yards ensure you pay for exactly how much wood volume you’re getting. This term is especially important when buying hardwoods, live-edge slabs, or custom-milled lumber where dimensions aren’t standard. While many DIYers might not use “board foot” in everyday projects, it’s good to know – you’ll often see it on price lists or invoices for cedar and other woods. If you ever request a custom cut of Eastern Red Cedar from a sawmill like Mountain Milling Co., they may quote the price in board feet. Now you’ll know how to interpret that and even double-check the math!

Understanding Board Feet: Lumber Volume ExplainedSquare Foot

A square foot (sq. ft.) is a unit of area, measuring a flat surface’s coverage. One square foot equals a 12-inch by 12-inch area (1 ft × 1 ft = 1 sq ft). Thickness is not included in square footage – it’s purely about surface area[4]. In lumber terms, you’ll use square feet when talking about covering surfaces: flooring, siding, paneling, decks, or any project where you need to know how much area the wood will cover.

How it’s calculated: It’s simply length × width (in feet). If you have measurements in inches, convert them to feet (divide by 12) or multiply length and width in inches and divide by 144 to get square inches in a square foot. For example, a board that’s 6 inches wide and 2 feet long covers (0.5 ft × 2 ft) = 1 square foot of area on a surface. A bigger example: a standard plywood or OSB panel is 4 feet by 8 feet, which equals 32 square feet of coverage[5]. That’s the area it will cover on a floor, wall, or roof.

Example: Imagine you want to line a closet with aromatic Eastern Red Cedar planks. If the wall is 8 feet high and 10 feet wide, that’s 80 square feet of area to cover. Knowing this, you can calculate how many cedar boards you need. Suppose each cedar plank gives 5.5 inches of coverage in width (which is about 0.46 feet) and is 8 feet long. Each plank would cover roughly 0.46 ft × 8 ft = 3.68 sq ft. To cover 80 sq ft, you’d need around 22 of those planks (because 22 × 3.68 ≈ 81 sq ft, a little over to account for cuts or waste). This is a simplified example, but it shows how square footage is used in wood buying guides – you figure out the area and then determine the materials needed.

Why it matters: Square footage is the go-to measurement for wooden surfaces. If you’re installing cedar siding on a house or putting down a cedar deck, you’ll calculate the total area to cover so you can buy the right amount of material (plus a little extra for waste or odd cuts). Lumber yards often list the coverage of their products in square feet. For instance, tongue-and-groove cedar boards might say “covers X square feet per piece.” Knowing your project’s square footage ensures you purchase enough wood and helps compare costs: e.g., one type of cedar siding might cost $X per square foot versus another type. In short, use square feet whenever you’re concerned with covering an area – it’s an essential part of any wood buying guide for projects like flooring, paneling, or siding.

Linear Foot

Measuring length with a tape –linear feetonly consider one dimension: length.

A linear foot (lin. ft.) – sometimes called a lineal foot – is simply a measurement of length. One linear foot is 12 inches of length. That’s it! Unlike board feet or square feet, a linear foot ignores width and thickness; it’s a one-dimensional measurement[6]. If you lined up a piece of lumber on a tape measure, every foot of it is a linear foot. This term is commonly used for materials sold by length, such as trim, molding, pipes, or dimensional lumber when priced per foot.

How it’s calculated: There’s no special formula here – you just measure the length in feet. Five feet of 2×4 board equals 5 linear feet, for example. If you have multiple pieces, you add up their lengths. For instance, if you have three cedar boards each 8 feet long, you have 3 × 8 = 24 linear feet of lumber in total.

Example: Suppose you’re building a fence and the total length is 100 feet. If the lumber yard sells Eastern Red Cedar fencing by the linear foot, you’d tell them you need 100 linear feet of fencing boards (perhaps a certain style or width). It doesn’t matter how wide those boards are – the price is based purely on that running length. Another example: say you need cedar trim around your living room. You measure all around and find you need 40 linear feet of trim. You can then buy, for instance, five pieces of 1×4 cedar trim at 8 feet each to get 40 linear feet. The width (1×4 means 3.5 inches actual width) isn’t part of the measurement – you’re paying for the continuous length of wood. Lumberyards might quote trim or molding at, for example, “\$2 per linear foot,” in which case 40 linear feet would cost $80.

Why it matters: Linear feet are used when only length is relevant to pricing or planning. This is especially true for standardized cross-sections. For example, cedar porch railings, baseboards, or crown molding might all be sold by the linear foot because their profiles (cross-sectional shapes) are standard – you just pay for how many feet you need. Using linear measurements makes it easy to estimate and communicate needs: you just measure the run or perimeter in feet and that’s what you buy. It prevents confusion between pieces of different widths or thicknesses; you’re focusing on “how long” not “how big around.” In project planning, thinking in linear feet helps ensure you buy enough length of material (so you’re not short when trimming out that cedar-paneled room, for example). Just remember that if the width or thickness changes, the price per linear foot might change too – but as long as you’re comparing the same product, linear foot pricing lets you scale up or down easily. When in doubt, ask the lumber supplier to clarify if pricing is by linear foot or by board/piece – they’ll often help double-check your calculations[7] to make sure you get the right amount of wood.

Air Dried Lumber

Air-drying lumber: Fresh-cut boards stacked with spacers (“stickers”) to allow air flow for gradual drying.

Air dried lumber refers to wood that has been dried naturally by exposure to air, without the use of a kiln. After a tree is sawn into boards at the mill, the fresh boards (green lumber) are stacked in layers separated by narrow sticks or spacers, a process called sticker stacking[8]. These stacks are placed in a covered area or outdoors, and over time the natural airflow and warmth gradually dry the wood. Air drying is a slow process – it can take several weeks to many months depending on the wood species, thickness, and weather conditions[9]. Sunlight, wind, and low humidity will speed it up, while thick boards or damp weather slow it down.

By the end of air drying, the lumber’s moisture content will have dropped significantly from when it was freshly cut, but it usually doesn’t get bone dry. Well air-dried wood typically reaches about 15–20% moisture content (MC) in many climates[10]. In other words, 15-20% of the wood’s weight is water that’s still in the cells. This is much lower than green wood (which often starts above 50% MC in some species), but it’s higher than the ~8-12% MC that is ideal for indoor use. Air drying will usually only dry wood to the equilibrium with the outdoor air – for example, here in Arkansas, fully air-dried cedar might stabilize around that 15% MC range if left outdoors long enough.

Example: If Mountain Milling Co. cuts a batch of 1-inch thick Eastern Red Cedar boards and stacks them in the yard over the summer, by autumn those boards may be air dried to a usable state for many projects. An air-dried cedar board is less likely to ooze sap or significantly shrink after you buy it, compared to a green board, because much of the excess moisture is already gone. However, if you brought that air-dried board indoors to use for interior furniture, it might still shrink a bit more or could possibly warp as it continues to dry to indoor humidity levels (which is why kiln drying is used for furniture-grade wood).

Why it matters: The drying method affects the stability and usability of lumber. Air-dried lumber is cheaper to produce than kiln-dried (since you’re using time and nature instead of energy from a kiln), and it’s often preferred for certain outdoor or rustic applications. For example, air dried lumber is commonly used for patio furniture, decking, fencing, and other outdoor projects[11]. In these cases, having lumber at ~15% MC is fine because the wood will live outdoors and continue to acclimate; also, a bit of remaining moisture can make the wood slightly easier to cut without excessive blade dulling. Air-dried cedar, in particular, retains the wood’s natural oils and color nicely during the gentle drying process. The trade-off is that air-dried wood is not as uniformly dry or dimensionally stable as kiln-dried wood. You might see a bit more movement (expansion/contraction) or the occasional piece that warped during the slow drying. When buying cedar lumber, if you see it labeled as “AD” or “air dried,” know that it’s got moderate moisture content and is generally intended for exterior use or projects where perfect stability isn’t critical. If you’re building something like a backyard shed, a raised garden bed, or a fence with Eastern Red Cedar, air-dried boards would work well and save you some cost. Just avoid using air-dried lumber for fine indoor woodworking unless you plan to dry it further. The good news: at Mountain Milling Co., our wood buying guide advice is that if you need help deciding (air dried vs. kiln dried), we’re happy to discuss your project’s needs so you get the right lumber.

Kiln Dried Lumber

Kiln dried lumber is wood that has been dried in a special chamber (a kiln) where temperature, humidity, and airflow are controlled. Instead of waiting months for nature to do the job, mills use kilns to dry wood much faster and more thoroughly. After initial air drying (or sometimes directly after cutting for softwoods), boards are loaded into a kiln. The kiln is basically like a giant oven with fans and vents – it circulates hot dry air around the wood and can even introduce steam or vent moisture out to carefully manage how the wood dries[12]. Over a period of days or a few weeks (depending on wood thickness and species), the lumber’s moisture content is brought down to a target level, often around 6–10% moisture for most quality lumber[13]. Kiln operators follow schedules to dry the wood evenly and avoid drying too fast (which can cause cracks).

By the end of the process, kiln-dried lumber is much drier than air-dried – typically somewhere around 8-12% moisture content for many types of cedar and pine, sometimes even as low as 6-8% for wood intended for indoor use like furniture[14]. This level of dryness mimics the indoor environment, so the wood will stay straight and stable when you bring it inside. An added bonus: the heat of kiln drying (often around 120-140°F) kills any insects or larvae that might be in the wood[15]. This is important for woods like cedar or oak that could harbor bugs; kiln drying ensures you’re not bringing unwanted pests into your home along with the lumber.

Example: Mountain Milling Co. prides itself on carefully kiln drying our Eastern Red Cedar boards for tongue & groove paneling and siding. For instance, if we take those same 1×6×8 boards and kiln dry them after air drying, we’ll bring them down to a stable moisture content throughout. The result is kiln dried cedar boards that are ready to install. If you were to build, say, a cedar dining table or some shelves for inside the house, you’d definitely want kiln-dried lumber so that once the piece is in your climate-controlled home, the wood doesn’t shrink or warp. Another practical example: cedar decking boards. A cedar deck should ideally be built with kiln-dried lumber. As one expert noted, if you use kiln dried cedar for a deck, you’ll have more consistent spacing between boards over time and you can apply a finish right away without waiting for the wood to dry out[16]. If you built the same deck with green or wet wood, those boards would later dry and shrink, potentially leaving larger gaps or even causing the boards to twist. With kiln-dried boards, what you see at installation is close to what you’ll get long-term (just allow for minor seasonal movement).

Why it matters: Kiln drying is all about stability and performance. For any woodworking or construction where precision counts – think interior flooring, cabinets, furniture, doors, or trim – using kiln-dried lumber is crucial. Wood at 8% moisture today isn’t going to suddenly crack or cup as it equalizes, because it’s already at the low moisture level typical of indoor environments. Kiln dried wood is also usually lighter (less water weight) and often cleaner – the controlled environment prevents staining or mold that sometimes can affect air-dried wood in humid conditions. You might notice kiln-dried boards are stamped “KD” with a moisture content specification (like KD19 means kiln dried to 19% or less, which is common for framing lumber). For Eastern Red Cedar products, “kiln dried” is a mark of quality that Mountain Milling Co. emphasizes: we kiln dry our tongue & groove and siding cedar to ensure consistent moisture content and to preserve the wood’s integrity in use[17]. The only downsides to kiln-dried lumber are a slightly higher cost (energy and time in the kiln add to production costs) and the possibility that very rapid drying can make wood a bit more brittle to work (though cedar generally remains easy to work with). In summary, if you want top stability and immediately usable lumber, go with kiln dried. It’s especially important for indoor projects or any wood that will be finished (stained/painted) right away. Our wood buying guide tip: use kiln dried cedar for things like indoor paneling, furniture, or decking, and you’ll have far fewer headaches with wood movement or finish issues.

(Side note: Kiln vs. Air isn’t always an either/or – some lumber, as we do in our mill, is first air dried and then finished in a kiln. This is a cost-effective way to get stable wood. The air drying removes a lot of moisture for free, then the kiln brings it to final moisture. All Mountain Milling Co.Eastern Red Cedar lumberfor interiors is kiln dried for your convenience and project success.)

Green Lumber

Green lumber refers to wood that is freshly cut and not dried. In other words, it still contains most of the natural sap and moisture from the living tree. When you pick up a green board, it often feels damp or cool to the touch, and it’s noticeably heavier than a dried board of the same size due to all that water weight[18][19]. For example, a green 2×4 of Eastern Red Cedar could have a moisture content around 25% or even higher, meaning a quarter of its weight is water (fresh-cut cedar can range roughly 24–29% moisture content)[19]. Green lumber may even “weep” a bit of moisture or sap, and if you smell it, it has the rich, strong scent of fresh cedar (in fact, cutting green cedar releases a wonderful aroma).

In practice: Boards straight out of the sawmill – say, a cedar log that’s been milled this week – are green. If you were to buy rough-cut green lumber, you might notice beads of moisture or that the boards are very flexible. Carpenters sometimes joke that green wood is so full of water you could almost wring it out. Green Eastern Red Cedar will have that vivid purple-red heartwood color with bright white sapwood, and it might feel a bit sticky due to natural oils and moisture. It hasn’t had time to shrink yet, so its dimensions are as cut, but be aware: green wood will change as it dries.

What happens as green wood dries: This is where the concerns come in. As green lumber loses moisture, it shrinks. And because drying is never perfectly uniform, different parts of a board can shrink at different rates, leading to warping (bending or twisting), splitting (cracking at the ends), or surface checking (little splits on the surface)[20]. Think of a sponge drying out – it might shrivel unevenly. That’s what can happen with wood. For example, if you build a bookshelf with green cedar boards, over time the shelves might cup or bow as they dry, and joints could loosen. Moreover, paint or finish won’t adhere well to green wood because of the moisture – it could peel or trap moisture under it. These are the reasons we usually avoid using green lumber for fine woodworking or indoor projects. It’s simply not dimensionally stable until it dries.

Are there times to use green lumber? Yes, actually. Green lumber can be useful or economical for certain situations. In the construction industry, pallets (the wooden skids used for shipping) are often made from green lumber – it’s cheap and the slight warping doesn’t matter much for a pallet’s function[11]. In outdoor construction, cedar fence boards are commonly sold green and installed while still somewhat wet. This might sound odd, but cedar fence pickets are usually thin (like 1/2 inch or so) and installed with gaps; as they dry in the sun, they’ll shrink a little, but because they’re so thin, they generally don’t crack badly – and any minor warping is not very noticeable in a fence. In fact, it’s an industry standard that many cedar fencing boards are sold green[21]. They’ll quickly air dry once up on the fence, and since both sides are exposed to air, they tend to dry relatively evenly. Another scenario: large timbers for outdoor use (like a rustic cedar post or beam) might be used green in a barn or pavilion, accepting that over time it will develop some cracks (often desired for a rustic look). Carvers or woodturners sometimes also work with green wood because it’s easier to cut, then they let the finished piece dry later.

Why it matters: If you purchase lumber and it’s described as “green” (or if no mention of drying is made, you should assume it’s green), you need to handle it differently. For woodworking projects, green lumber is generally a no-go unless you plan to dry it yourself. It can lead to disappointment when that beautiful cedar table warps or the joints pop open as the wood dries. However, green lumber is usually cheaper and more readily available (since it skips the drying steps). So, if you’re doing a project where some movement is acceptable or the wood can dry in place, green lumber can save money. The key is to know what you’re getting into. At Mountain Milling Co., we typically do not recommend green lumber for most end-user projects – that’s why we invest in proper drying. But if you ever do want to buy green cedar (say, for a landscaping project or you want to mill and dry it yourself), it’s important to stack and store it properly. Keep it out of direct sun, use stickers between boards, and let it slowly air dry under shelter to minimize cracking. Always leave room for the wood to shrink – for instance, if building with green wood, you might tighten bolts later after it dries, or install boards a touch snug knowing they’ll contract.

In summary, green lumber is the starting point of all wood, and it’s great for certain uses like pallet wood or quick outdoor builds, but it’s something you usually dry (by air or kiln) before using for precise work. Knowing that green means “full of moisture” will help you make the right buying choice: if you see a low price on cedar but it’s green, factor in that you might need to dry it or accept the quirks that come with it. And when in doubt, ask – we’re happy to clarify whether a given Eastern Red Cedar product is green, air dried, or kiln dried so you can make an informed decision.

Conclusion & Call to Action: Understanding terms like board foot, square foot, linear foot, and knowing the difference between air dried, kiln dried, and green lumber will make you a much savvier wood buyer. You’ll be able to walk into a lumber yard (or browse our Mountain Milling Co. product list) and confidently ask for what you need – whether that’s 100 board feet of kiln-dried Eastern Red Cedar for a home project or 200 square feet of cedar siding. Remember, these terms ensure everyone is on the same page about measurements and wood quality, so don’t hesitate to use them in your planning.

If you’re still unsure about calculations or deciding which type of lumber is best for your project, we’re here to help. Mountain Milling Co. prides itself on customer education and support – think of us as your partner in getting that DIY job done right. Feel free to reach out with questions about lumber sizing, moisture, or anything else. Not sure how many board feet of cedar you need for a patio bench, or whether you should use air-dried vs. kiln-dried wood for your application? Ask us! We’d love to help you figure it out and provide a free quote or advice. Purchasing wood should be the easiest part of your project, and with the knowledge you’ve gained from this guide (and a little backup from our team), you’ll get exactly what you need.

Happy building, and don’t hesitate to contact Mountain Milling Co. for any of your Eastern Red Cedar lumber needs – we’re just a call or message away, ready to assist with expert guidance on wood selection, sizing, and more. Your successful project is our priority, so let’s build something great together![7][17]

[1][2][3][4][5][6] The Difference Between Board Foot, Lineal Foot, and Square Foot

[7] Lumber Lingo: Understanding “Board Feet” – J&W Lumber

[8][9][11][13][14][18] Hardwood lumber is often called either “Air Dried,” “Kiln Dried,” or “Green”. What’s the difference? – ETT Fine Woods

[10] FNR-37 – Purdue Extension

[12][15][16][19][20][21] Know the Difference: Green or Kiln Dried Lumber

[17] Mountain Milling Co Website Text.docx